By Ovie Oghenejobo, Fadesola Ojeikere, Dana Mortenson and Fernande Raine

When President Trump announced plans to establish a government body — the 1776 Commission — to promote “patriotic education” in America’s schools, we were concerned by the intentions behind this move; but it also got us wondering: What is a ‘Patriotic Education”? As educators, we have our own ideas and have been talking about what that could mean ever since. Though President Trump will not serve a second term and go on to see the 1176 Commission through, this election made abundantly clear that educators and students must learn to engage in civil discourse in a holistic and inclusive manner.

A patriotic education teaches students to engage in the habits of democracy. That means engaging in civic — and civil — discourse, including with people who hold radically different views. And it means teaching students to study their country’s real history, with all of its pain, so that we can heal and make it better. With a new incoming administration, the time is ripe to think critically about the future of our civic education.

Encouraging civil discourse and truthful history requires a fundamental shift not just in what we teach, but how we teach. We became educators to raise young people to be citizens of democracy. We believe in education that challenges students to think, analyze, and contribute to the conversation rather than just passively receive information. We believe in encouraging students to ask questions and find answers, because not only does this help them understand and retain subjects, it also builds the critical thinking skills that they will need to adapt, innovate and thrive in a world of rapid change.

Currently, most students learn a monolithic, whitewashed version of history through standardized textbooks. The goal of these textbooks may be to weave a common national identity, but they usually do the opposite: by minimizing diverse voices and perspectives, they promote an identity that’s fundamentally exclusive. National nostalgia is not the formula to prepare thoughtful and informed citizens.

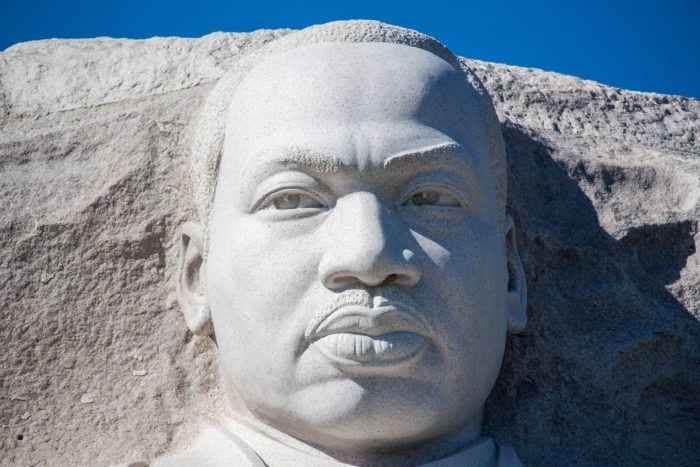

A truly patriotic education that aims to teach students about our country, and equips them to improve it, would invite them to lead their own conversations on America’s complex past and its reverberations in our present. Education should help young people wrestle with the fact that our nation grew on complicated roots, and that from these roots sprang both radical ideas of freedom and justice, but also great inequities and suffering. It should teach them to think critically about whose stories we honor and what “truth” means in history when all stories aren’t equally heard or valued. Students who think critically about the parts of American history that inspire shame, as well as those that inspire pride, will be better positioned to lead the next chapter of the American saga.

These kinds of conversations can be hard, but they are possible. Indeed, they already are happening at Great Oaks Legacy Charter school in Newark, New Jersey where students have been learning about the history of Cesar Chavez and farm workers. Soon they will turn their attention to the poor conditions farm workers continue to endure and will analyze which demographics consistently work in lower-wage jobs and how systemic racism is an impediment to a better quality of life. Ultimately, these students will define what justice looks like for communities based on this information.

These challenging discussions can even draw in the larger community as is happening in Kansas City, where teachers are wrestling alongside museum educators through how to approach systemic racism. Via their Learning Collaborative, they are creating powerful local resources. For example, the Johnson County Historical Society designed the first local learning journey for teachers and students into the topic of redlining, offering learners the opportunity not only to explore what the effect of racist housing policy was in the past, but how those policies shaped the very neighborhoods in which they live today.

A patriotic education also would equip young people to participate in, and one day lead, our diverse, global, modern society. Technology has made our cultural and economic borders more porous. Affordable products arrive in your local Target via supply chains and workforces spread across continents. The constant movement of people among and between countries has become a defining trait of our modern society. Our schools must teach students to navigate these global complexities.

A patriotic education is one that positions young people to envision and work toward a better America — to learn and analyze so we can make our world a better place. This is happening at Byram Hills High School — a school that partners with World Savvy, a national education nonprofit reimaging K-12 education for a more diverse, interconnected world — in Armonk, New York. Educators there ask students to identify an issue in their community, gather data, seek out multiple perspectives, and design and execute a project to address it. This fall, they took on increasing voter participation in the November election.

Many of our country’s founders were aspirational. While they set out core values for the United States in our founding documents, they recognized that the pursuit of those values would have to change over time. They would have eschewed an uncritical celebration of history as an impediment to achieving that change. Ultimately, a patriotic education should build a strong connection between our nation’s youth and these bold ideals of our founding because so much of the work our founders envisioned still lies ahead of us.

Along with World Savvy, Got History, and all other organizations that are fighting for better history teaching, we call on all historians, parents, and educators to engage in this critical conversation and build a movement for education that matches the legacy of our country, the complexity of our world and, most importantly, the needs of our students.

Ovie Oghenejobo is assistant principal in the Lee Summit School District in Kansas City and a founding member of the Kansas City Learning Collaborative. Fadesola Ojeikere is a director of curriculum and instruction at Great Oaks Legacy Charter School Network, co-founder of the Teach For America Alumni Board and a World Savvy Ambassador. Dana Mortenson is co-founder and CEO of World Savvy. Dr. Fernande Raine is co-founder of got history?

Dana Mortenson is the Co-Founder and CEO of World Savvy. Dana is an Ashoka Fellow, was named one of The New Leaders Council’s 40 under 40 Progressive American Leaders, and was winner of the Tides Foundation’s Jane Bagley Lehman award for excellence in public advocacy in 2014. She is a frequent speaker on global education and social entrepreneurship at high profile convenings nationally and internationally, and World Savvy’s work has been featured on PBS, the The New York Times, Edutopia and a range of local and national media outlets covering education and innovation.